New Research on Women’s Land Rights

A Mokoro Seminar

Zoe Driscoll

3 December 2015

/

- 1 Comments

Mokoro has a long history of working on land issues, and our consultants have between them decades of experience working to strengthen and support ordinary men’s and women’s land rights. This has not always been easy. In the past, land rights have often been overlooked by the development community, in part because they are difficult to measure. However, with a newly framed international agenda on land rights, the current context looks much brighter, and there is now a real opportunity to advocate and inform global policy on women’s and men’s land rights. In view of this two of our Principal Consultants, Robin Palmer and Elizabeth Daley, recently introduced a Mokoro seminar on “New Research on Women’s Land Rights”, aiming to identify areas in which research could contribute to current debates on women’s land rights and to critical issues for action and lobbying.

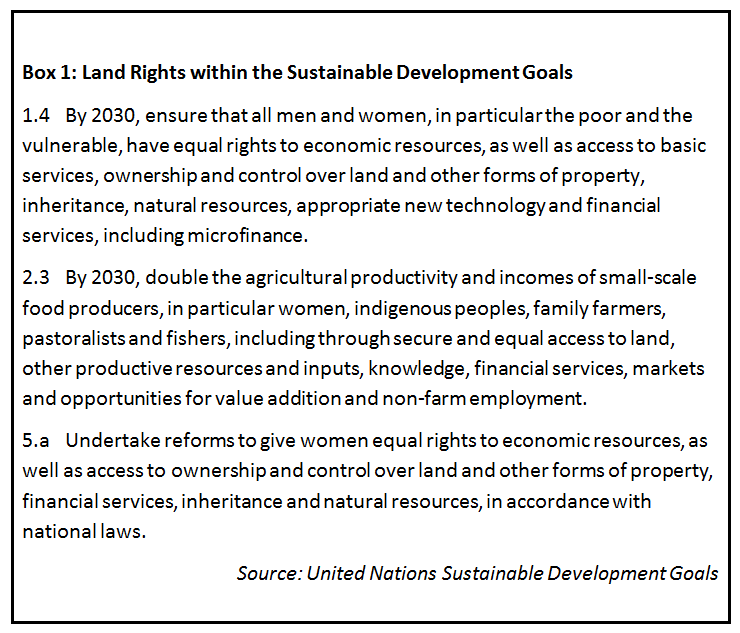

In September 2015, world leaders at the UN Sustainable Development Summit endorsed a new set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and tackle climate change by 2030. Within the SDGs, land rights are captured within the targets falling under three global goals, namely Poverty Eradication (1.4), Food Security (2.3) and Gender Equality (5.a) (see Box 1). Through this, critical gender issues such as women’s access to land have been recognised, on the grounds that women’s land rights can leverage progress on a number of critical overall development goals, including food security, child nutrition and poverty alleviation.

As implementation of these new SDGs begins, the focus of policy makers has turned to discussion of the indicators that will be used to measure progress, including on land rights. A land rights indicator is needed that will capture gendered dimensions of all people’s rights to land, property and natural resources, and provide countries with a tool to monitor their progress in achieving their targets, as well as enabling the global community to follow the progress that is being made. Sex-disaggregated data on land rights will prove critical to this. The development of the post-2015 framework thus provides a historic opportunity to push the evidence base forward on land rights to inform global and national agendas and policies and bring women’s land rights to the forefront. One such effort is being made by the Global Land Indicators Initiative – a coalition of donor agencies and civil society organisations that has proposed an indicator to measure the “percentage of women, men, indigenous peoples, and local communities with secure rights to land, property, and natural resources, measured by (a) percentage with legally documented or recognised evidence of tenure, and (b) percentage who perceive their rights are recognised and protected”.

Within this overall context, following the adoption of the SDGs there is now a real opportunity to advocate and inform global policy on women’s and men’s land rights. Mokoro’s seminar on “New Research on Women’s Land Rights” took place in this context and had an encouraging atmosphere throughout, with optimism from participants that context-specific, long-term research can unearth strong evidence to convey powerful messages. The seminar specifically aimed to identify contributions that the research from our speakers, as well as from the wider audience, could make to current debates on women’s land rights, and to highlight critical issues for action and lobbying in the context of the newly framed international agenda on land rights.

The seminar was held in Oxford on 10 November, with over thirty participants from a range of NGO, academic and consultancy backgrounds. Helen Dancer from the University of Brighton kicked off the morning, talking about her fieldwork in Tanzania, researching women’s claims in the land tribunals of Arusha. Kristina Lanz, a PhD student from the University of Bern, then spoke about her recent fieldwork in the Volta region of Ghana, looking at the impacts of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) on households.

Helen Dancer, a former practicing family lawyer, conducted her ethnographic fieldwork between 2009 and 2010, followed by further shorter visits in 2010, 2011 and 2014. In a region with a history of land-based conflicts and pressures on land from mining, tourism, and other factors, Helen looked at micro-level land disputes, studying the issues that give rise to women’s legal claims and tracing the progression of claims from their social origins, through the legal processes. The key issues for women were those of inheritance and the sale of land without consent. Helen saw the importance of the social context and the role of family and community leaders in the process as crucial. In order for women to be able to claim rights, they need people to support them in the process. In a country where women are still discriminated against, for example in land inheritance, without the support of key community elders and family leaders in bringing their cases to court and recognising their rights, they have little success in court.

Helen made three key recommendations with regard to the wider lessons around the sustainable development goals. First, there is a need for gender analyses to be fully integrated into law and policy formulation on land, marriage and inheritance matters. Second, access to justice initiatives must address the social and institutional pathways that help and hinder women in making legal claims. Finally, there is a need to recognise that equal access to justice for all requires training and consciousness-raising for lawyers and adjudicators, at all levels of the legal process, on the existence of implicit and explicit gender biases and social power relations within the litigation process itself, which stems from her observation that the evidence that is valued most by the court (e.g. minutes of clan meetings) has its own gender bias.

Kristina Lanz, who is in the second year of her PhD, carried out five months’ participatory research in Ghana’s Volta region, from which emerged some demoralising findings, highlighting the importance of long-term research in gaining an understanding of the power struggles that were going on in the region. She talked about the implementation of a major land acquisition by Ghana Agro-Development Company (GADCO), who grow rice for the national market, as well as the particular role that customary leaders played in this process and the various exclusions and inclusions the investment created. The investment by GADCO has been described as a model for best practice inside and outside Ghana, particularly in terms of efforts towards women’s empowerment. However, the 2.5% of the company’s monthly sales revenues that are paid into a community development fund have not been seen by most people in the community and many have also been excluded from their access to land and important resources. Furthermore, Kristina found amongst other things, that: compensation was only received by locally important people; women employed by the investors were only hired for highly flexible casual labour positions; and the company cleared trees on common land, thus stripping local women of one of their main income-earning opportunities. Local people found that involving government authorities, and engaging in court cases, was futile, as both the chiefs and GADCO had powerful connections, and many people suspected that the Government and courts were being bribed. Kristina’s research thus highlighted the difficulties in the implementation of an LSLA, and in this case presented the sad story of a company using its partnership with traditional rulers to claim inclusivity for a whole community, whilst the chiefs reap the benefits and use their power to combat any resistance from the community. It brings forward questions about how LSLAs can be managed, to ensure that local people see the benefits of investments, and in the wider context the importance of strengthening community organisations to recognise their rights.

The discussion that followed these two case study presentations was very lively and continued on well into lunch. It brought to light many more cases that highlighted the complexity of local social contexts in determining community rights, with examples given from across Africa, South-East Asia and Latin America. The seminar discussion emphasised the importance of continued rigorous and long-term research at the community level to provide locally specific solutions for policy and law makers. Participants concluded that it is also important that there is utmost transparency, so that the truth about different LSLAs can be exposed. Academics play an important role in representing communities and, as Robin Palmer pointed out, as activists for community rights – yet, at the same time, it is important for their neutrality and independence to be maintained.

For further information on the two case studies presented at the seminar, please see the speakers’ presentations, downloadable from our website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A great write-up by Zoe of a great seminar! I really enjoyed all the lively debate at our recent meeting on new research on women’s land rights, so many issues came up and so much of relevance not only for our WOLTS project but also to wider initiatives like the Global Call to Action on Indigenous & Community Land Rights #landrightsnow