Putting research into action – One muddy step at a time

Elizabeth Daley

30 January 2020

/

- 0 Comments

I write this blog as our project team embarks on a fifth year of work on women’s land tenure security (WOLTS) with pastoral communities in mining-affected areas of Mongolia and Tanzania. Just before Christmas 2019, we were in Mundarara village in northern Tanzania. Exceptionally heavy rains made getting around much more challenging than usual. Locals travelling on foot had to make wide detours to avoid getting bogged down in waterlogged grazing land, and it took everyone much longer to get to the village primary school for our long-planned training day.

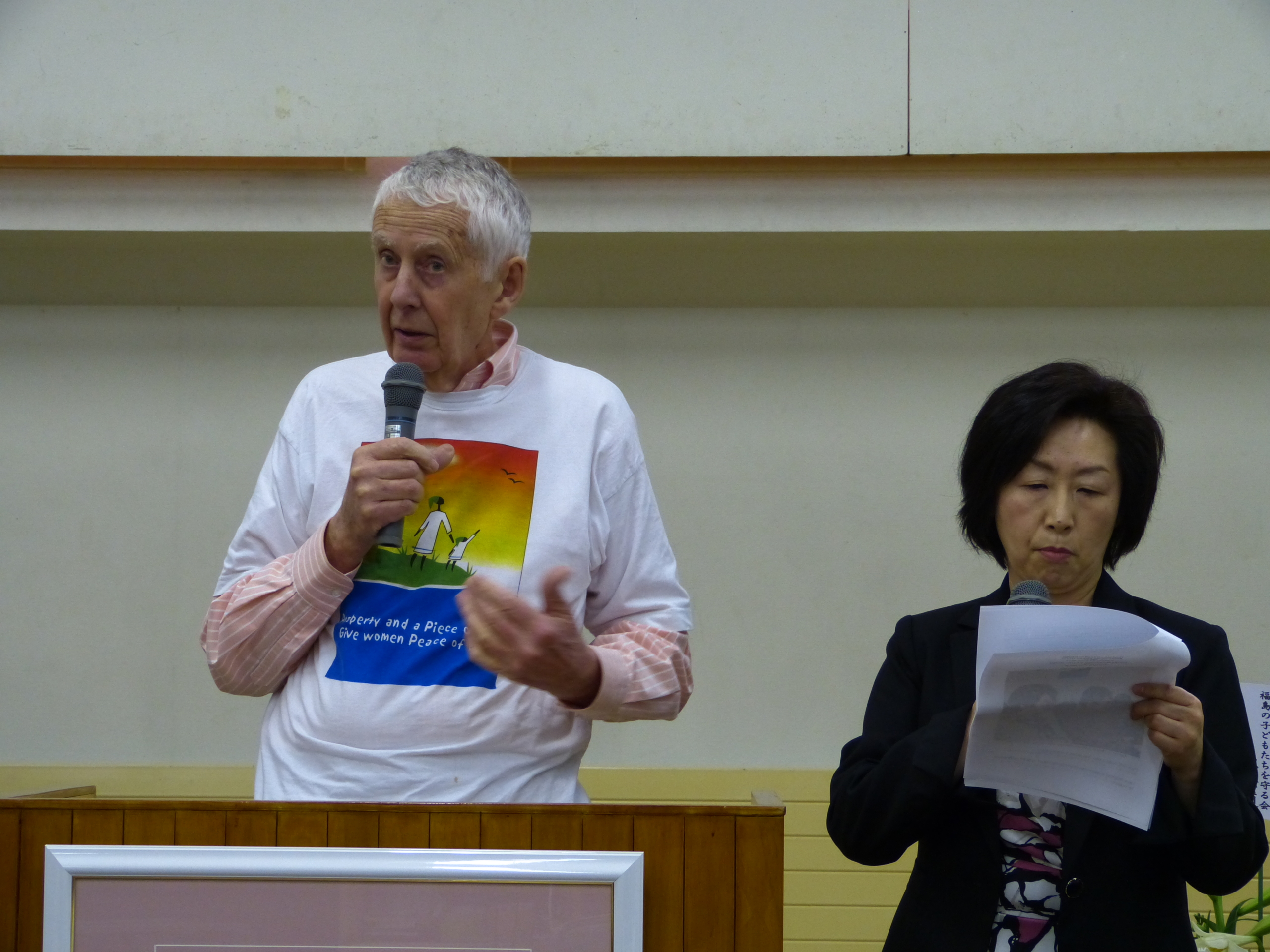

© J. Grabham, WOLTS Team

The mud and the unusually heavy rains reminded us – as if we needed reminding – that climate change is indeed real. Rural communities in places like Mundarara are struggling with land issues on so many fronts, and increasingly variable weather patterns only add to the long list of land governance problems. Threats to community land rights – especially to the land rights of vulnerable communities, and of vulnerable people within all communities – will only escalate as the effects of climate change multiply in unpredictable ways. So it will become more and more important for local communities, especially women and other vulnerable groups, to play an active part in managing their land and natural resources.

Our goal with the WOLTS project from the start has been to make a real difference in communities like Mundarara. We seek tangible improvements in women’s tenure security through strengthening the evidence base on what works and building capacity to implement it. We’ve done this through action research – or (perhaps more accurately) through living, active research.

We have taken a highly participatory and community-focused approach that supports the land rights of all vulnerable people within a community, deliberately seeking to make it ‘win-win’ rather than ‘either/or’. We have included both men and women every step of the way.

During Stage 1 of WOLTS in 2016 and 2017 we carried out a baseline survey and a first phase of participatory research, and then held a series of community feedback meetings to test and validate our findings. Our approach was highly iterative, with the design of each round of field research building on what we had learned previously, what gaps had emerged, and critically, what the community told us they needed. By the end of Stage 1 we had uncovered a host of new understandings about the intersection of land, gender, mining and pastoralism, as shared in our country reports on Mongolia and Tanzania.

In response to Stage 1 findings, and encouraged by the communities themselves, we started a ‘champions’ training initiative in gender equity for a mixed group of dynamic and respected community members. We will carry out a second round of training followed by feedback surveys to help us assess what impact they’ve had in our pilot communities and hope to publish the findings later this year.

There have been some pleasant surprises already. For example, our male champions have told us they now see gender equity as something desirable that the whole community can win from, rather than as something only for female champions or even something to fear. As one traditional male elder in Tanzania told us: “I like knowing that I am a free citizen who has a role to support marginalised groups like widows and girls.” Another said: “I was surprised to learn that I, as a traditional leader, have a role to make sure that there is a practical gender balance in my community…I’m now insisting to give a chance to women in everything we do.”

We have also seen that careful and highly participatory facilitation and community engagement carried out under the leadership of our local partner organisations is vital in terms of confidence to speak out. An elderly Maasai woman in Tanzania put it thus: “I was surprised that women were not afraid to speak about their challenges in front of men in the training.”

Equally, our process has helped champions to gel into a committed group of influential local citizens, equipped with the right skills and knowledge to make positive change in their communities. In Mongolia, one young woman told us emphatically: “We will succeed if we work as a team of champions…we have even created a Facebook group chat and we are using it a lot, it’s very useful.” Last year these Mongolian champions mobilised opposition to a new mining operation in their soum (district) centre using their Facebook group chat to coordinate and share information. Within a matter of months the mining operation had shut down.

Finally, we have seen how much relationship-building and long-term commitment matters for real change. Outside organisations that keep going back to communities after their research is complete remain few and far between; even those that go back at least once to share initial findings are not common. Knowledge is power, so giving back knowledge gained from people’s openness to talk to outsiders is a crucial step in empowering them to change their own destinies.

When I went to visit a disabled woman in southern Tanzania after interviewing her multiple times back in 1999, she actually thanked me “for asking me all those hard questions”. “You really made me think differently about my life,” she added. “Now I have new ideas and new plans for the future.”

Twenty years later, in a vastly more integrated world, facing a climate catastrophe on a scale I could barely conceive of back then, the power of living, active research remains just as strong – and even more necessary. In our own small way through our WOLTS work we are inspired by the feedback from our champions – that they feel empowered to claim and defend their land rights, not just from mining companies and investors, but from other threats to come. Putting research into action, one champion, one community, one muddy step at a time.

Elizabeth is a Mokoro Principal Consultant and is Team Leader of the global Women’s Land Tenure Security (WOLTS) project.