Peace in Mozambique 20 years ago

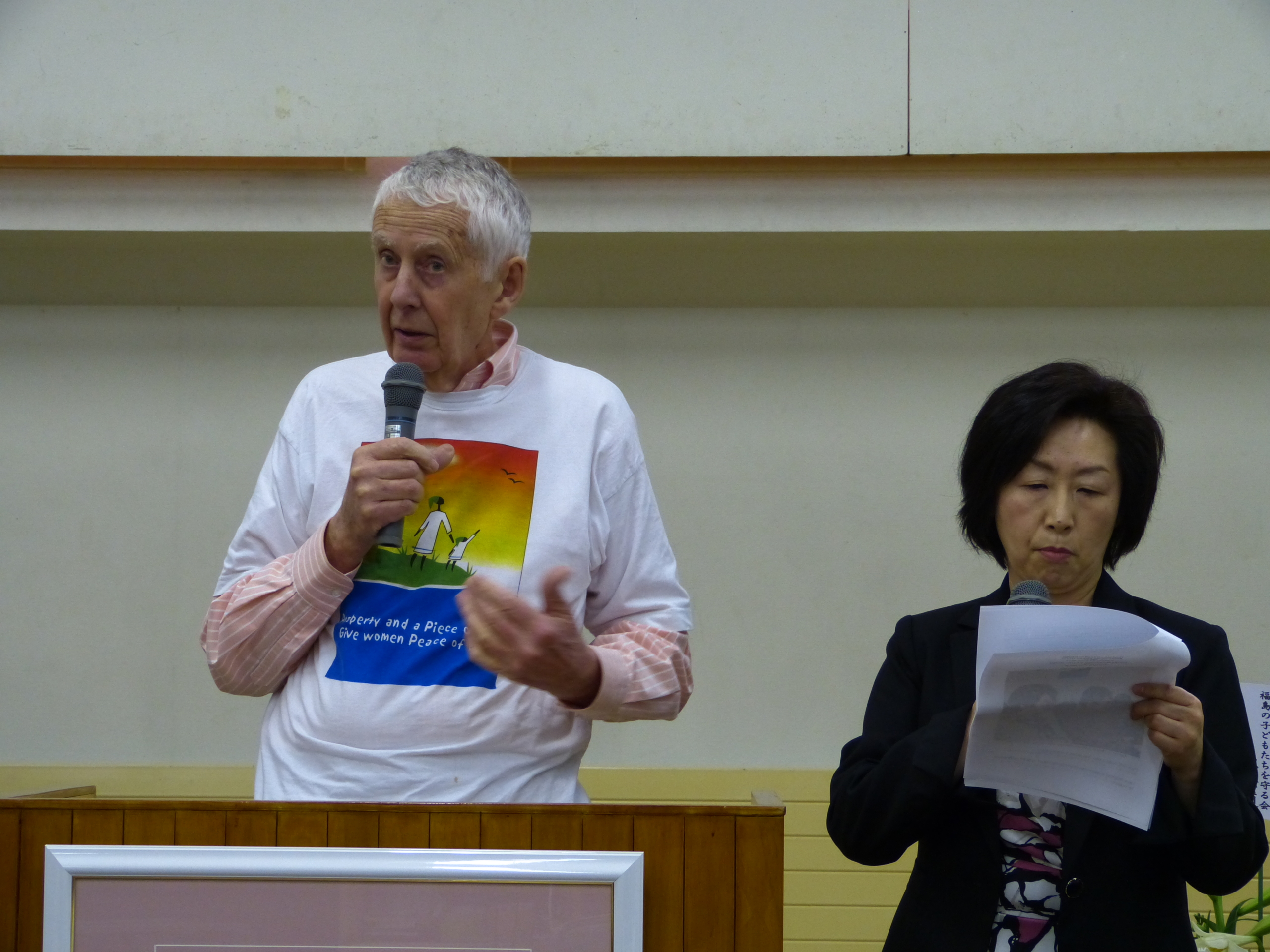

Robin Palmer

18 October 2012

/

- 0 Comments

In the previous Mokoro Newsletter, Daniela Huamán Rodríguez wrote engagingly about her ‘Unexpected Aventura Moçambicana’ on women’s land rights with Martin Adams and Liz Daley. In recent Mokoro seminars, Chris Tanner and Joe Hanlon have shared with us their long experiences of that country.

On 4 October, Mozambique celebrated the 20th anniversary of a peace agreement which ended a bitter 15 year civil war, fuelled by the Cold War and apartheid South Africa. Since that date, the country has enjoyed 20 years of peace. It is certainly an occasion to celebrate.

I had the great good fortune to have travelled in Mozambique, as Oxfam GB’s Oxford-based Regional Manager, just 6 weeks after that peace agreement. It was an unforgettable visit. I wrote at the time:

‘A guerra acabou’ (‘the war is over’) people keep telling you in Mozambique. A country which has been ravaged and almost destroyed by over a decade of civil war now finds itself at peace. It is a remarkable peace and the transition that has taken place so quickly is equally remarkable.

It is in a very real sense a people’s peace. True, the politicians signed a long overdue peace treaty in Rome in October, but by then people were already making peace at a local level. They are continuing to do so now and hopefully will continue to build peace in the crucial year that lies ahead.

People have made peace by going home to their places of origin in their hundreds of thousands without waiting for some official repatriation scheme to be launched for the millions of internally displaced and refugee populations. They have also deserted in large numbers from both armies and have gone home. These phenomena are taking place throughout Mozambique, but are especially striking in the country’s most populous and strategic province, Zambézia. They are beyond anyone’s capacity to stop them, and sensible administrators don’t even try. It is as though a whole people has said: ‘we’re tired of the war, we’re going home, and nobody is going to stop us.’

The highlight of my 1992 visit was travelling by road – which was again possible – to Mocuba and Alto Molocue with Agostinho Chirrime and Ilidio Candieiro from Oxfam’s Zambézia team. On 16 December we drove the 185 km north from Quelimane (the provincial capital) to Mocuba. I was immediately struck by the sheer normality of everything – no soldiers, no guns, plenty of people in lorries travelling in both directions, people selling things by the side of the road – pineapples, guavas, coconuts, mangoes, charcoal. The road itself was in amazingly good condition and all the bridges were intact. We travelled through stretches which were virtually uninhabited, as the war had forced a concentration of people into relatively safe areas. What was strikingly missing was large numbers of people walking or cycling along the road, carrying things from one place to another, or children going to and from school.

Mocuba is situated at the crossroads within Zambézia. Lots of people were passing through. There were plenty of motorbikes. The shops had a few things in them, but prices were beyond most people’s capacity to buy. The market was extremely busy and there were lots of second hand clothes. On sale were imported rice and beans (in a country that grows both!), American yellow maize, and fish. We walked around at sunset, just talking to people and asking questions. It felt deeply satisfying because during the war this had been quite impossible for foreigners and, at times, for Mozambicans working for international organizations. (You typically flew from the provincial capital shortly after dawn to a district centre, rapidly did your business, and then had to fly back before dusk).

We had gone to monitor and follow up seed distributions and had not intended to make contact with Renamo (the rebels). But in Mocuba, over lunch, they made contact with us, in the form of Carlos Francisco Mapuanha. He was a school teacher and Renamo’s local Head of Information. He said Renamo was determined to demobilise and to implement democracy. They believed they would win an election, but were prepared to form an opposition if they lost.

In Alto Molocue we met Bernado Nyhamphaza, who worked for Renamo’s Information Department at the national level and had been up there for the past 4 months, recording traditional songs and dances and doing interviews because he felt there was a danger of the people’s history being lost. Neither man conformed to the stereotypical Renamo image. Agostinho, Ilidio and I found ourselves somewhat taken aback to be talking to intelligent, articulate, quiet spoken, moderate people, who also seemed fully able to understand our attitudes and concerns.

Sr. Nyhamphaza said he was optimistic that the peace would last because, unlike in Angola, the war was not regionally based, as both Frelimo and Renamo had supporters in all the provinces and in all ethnic groups. He was concerned that the international observers had not yet arrived, but felt the relationship between Frelimo and Renamo was now good. This was evidenced when we were joined by Major Alface, head of the government army. The two clearly enjoyed an easy, relaxed relationship. We ran into a small Renamo group which had just arrived. They were moving, with their arms, from their main base to another. The striking thing was that no one on a busy Saturday morning paid them much attention.

Responses to these initial contacts were remarkably quick. The following week, Agostinho was invited by Renamo to travel to their zones and he soon began a distribution of cloth and blankets.

In my report at the time I wrote:

Renamo cannot be ignored, or wished away. They are signatories to the Rome peace agreement. Lasting peace will not come to Mozambique unless Renamo is fully brought into the peace process. International agencies such as Oxfam have an important role to play. Until the war ended, it was not possible for agencies to work on both sides. Now it is, and it is crucial that they all work in a non-partisan way in responding to humanitarian needs so as to help consolidate the peace. Encouraging, supporting and strengthening the peace process must be the major criteria by which Oxfam and others judge their proposed activities over the coming year. If the peace fails, there will be no development.

Mercifully, the peace has not failed.

But, on 5 February 1993, Agostinho and Ilidio were in a vehicle travelling towards a Renamo zone. It detonated a landmine and Ilidio was killed. It was a terrible tragedy, illustrating all too well the new dangers of working in a post-war situation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.