40 Years of Land, Roots and Myths

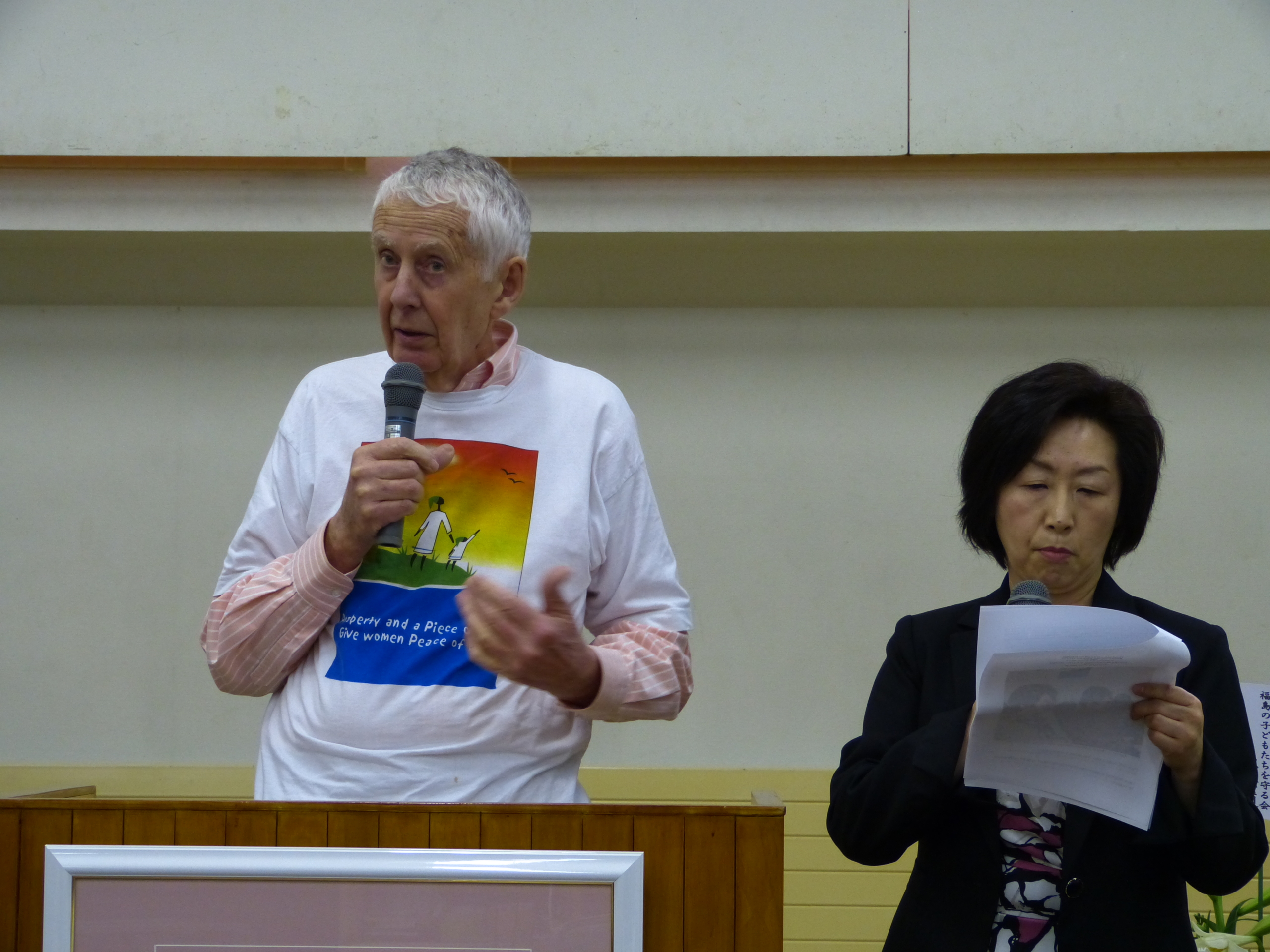

Robin Palmer

20 December 2017

/

- 0 Comments

Just over 40 years ago, in September 1977, James Currey, then still with Heinemann Educational Books, published two academic books of mine. The first was Land and Racial Domination in Rhodesia, based on my 1968 PhD. The second was a collection which I co-edited with Neil Parsons, The Roots of Rural Poverty in Central and Southern Africa.

The books were inspired by eight wonderful, exciting years as a lecturer in African History at the University of Malawi (1969-71) and the University of Zambia (1971-77). They were new universities, unconstrained by tradition. It was brilliant to be able to teach students about the current research which my colleagues and I were undertaking. Of course no one writes in a vacuum. What I saw as an undergraduate and a cricket and football player at the University College of Rhodesia (1960-65) was a countryside rigidly divided on racial lines. In the sparsely populated highlands around the capital, there were huge, manicured family farms of 3,000 acres owned by whites, many of them recent (post-1945) arrivals, and often growing tobacco, which then had a guaranteed market in Britain, which could not afford to buy American tobacco after 1945. They employed cheap black farm labour. They seemed the very picture of modern, progressive farming.

Beyond these white highlands, the bulk of the country’s black population lived in what were called, quite accurately, native reserves. These were by contrast densely populated, held under some form of customary ownership through chiefs, and were often badly eroded, evoking a sense of crisis. A casual observer of these ‘two nations’ might reasonably have deduced that white Rhodesians were excellent farmers, while their black compatriots were utterly hopeless. And such an observer might draw similar conclusions from right across Southern Africa. But that would completely ignore the history. And it was that history which I and others were determined to write. And in that writing we sought to demonstrate that peasants can still do it – and they had done it in the past.

What that history revealed was that a huge amount of social engineering and political repression had gone into creating the situation of 1960. When whites began pushing into the interior of Southern Africa in the late 19th century in search of mineral wealth, they created many new markets. And it was overwhelmingly black peasant farmers who responded positively to those markets, as Neil Parsons and I demonstrated in our Roots of Rural Poverty. The fly-leaf on that book captures very well what we were trying to do:

Why are African nations so poor today? In this book historians of a new generation look back and rediscover the history of peasant prosperity and subsequent impoverishment in the eleven states from Zaire [now DR Congo] to South Africa. They question the conventional wisdom of many development planners who have blamed poverty on the stagnant traditionalism of rural Africans. This is social history with economic and political dimensions, examining the impact of capitalism and colonialism on rural societies. Here is historical evidence that has too often been ignored and forgotten. This history has profound significance to students of all branches of social science, and for everyone concerned with understanding the present and planning the future of Central and Southern Africa.

In my own book, Land and Racial Domination, I also demonstrated that when mining in Rhodesia failed to develop as profitably as Cecil Rhodes had hoped, his governing (private) British South Africa Company decided to attract white settler farmers to the country. And so began a long process which involved the grabbing of the best land, the eviction of blacks into outlying native reserves further from markets, the creation of infrastructure to support the settlers, the heavy subsidisation of white farmers, controlled and segregated markets for maize, and the granting of political power to the white settlers and with it the ability to defend their economic interests. Similar processes took place elsewhere in Southern Africa.

We wrote about this hidden peasant history because it was important in its own right, but also, as we said in the introduction to Roots, explicitly to challenge a number of white myths about African agriculture. Sadly, many of these myths are still alive and well in South Africa, Zimbabwe and many other parts of Africa today.

This was brought home to me vividly on 27 November when I attended a meeting in Parliament of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Agriculture & Food for Development, addressed by the Director General of the FAO, ostensibly on the theme of The future of agriculture and the role of family farmers. After over an hour of talk and discussion confined totally to technical issues, I rose to my feet, mentioned my Roots of Rural Poverty book, with its focus on the history and politics of land, and asked why had there been no mention either of the global land grab and its impact on Africa or of the fact that so many of Africa’s elites, at both national and local levels, have become corrupt and have absolutely no time for family farmers.

Robin Palmer

The elites forget or ignore the fact that under World Bank-promoted structural adjustment programmes, African governments were not allowed to offer any support to small-scale farmers. Hence when Southern Africa was finally liberated, would-be black farmer beneficiaries of land reform in South Africa were denied the kinds of support which historically had been given over many decades to their white counterparts.

Africa’s elites also now seem wedded to the belief that the answer lies in bringing in foreigners who know how to farm properly and in offering them large concessions of land, with money of course disappearing into back pockets.

In many respects we seem to be heading back to colonial times, to a world which Cecil Rhodes would immediately recognize.

Maybe it’s time I wrote some more books!

You must be logged in to post a comment.