Researching Change and Continuity in Rural Ethiopia

The WIDE Research Project

Catherine Dom

14 July 2014

/

- 0 Comments

The WIDE (Wellbeing and Illbeing Dynamics in Ethiopia) research began in 1994 when Pip Bevan, sociologist working at the University of Oxford, and Alula Pankhurst, anthropologist working at the University of Addis Ababa, obtained funding to research fifteen rural communities. These had been selected by economists from the two universities to exemplify different types of agricultural livelihood system in which to conduct the first round of what became known as the Ethiopian Rural Household Survey (ERHS). Alongside the survey, Pip and Alula designed a comparative, protocol-guided qualitative research project involving Ethiopian field workers in the fifteen communities. This project, which became known as WIDE1 at a later stage, resulted in fifteen “village profiles” describing what these villages looked like a few years after the EPRDF took power from the Derg.

In 2003 Pip and Alula, with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council through the University of Bath, were able to revisit the fifteen communities and visit five more – three that had in the meantime been added to the ERHS panel by the economists, and two agro-pastoralist sites studied in the mid-1990s by Ethiopian social anthropologists. In this round, which later became known as WIDE2, Pip and Alula began to be interested in finding out what interventions were being implemented by external actors (government, donors, NGOs) in the communities and what the effects of these interventions were.

I met Pip and Alula around that time. Throughout 2003–2008 the three of us regularly discussed the uniqueness of the village-level perspective adopted in the WIDE1 and WIDE2 projects. Sometime in 2009 the idea emerged of proposing to conduct a third round of fieldwork in the same twenty communities. Unlike the previous two rounds conducted in academic contexts, this time we wanted the research also to be relevant to policymakers and practitioners in Ethiopia. Our starting point was that while over the years since 2003 Ethiopia had seen high economic growth rates, expansion in services and ‘home-grown’ political reforms, the impacts of these changes at local rural levels were not well known. We wanted to conduct research that would address this knowledge gap – by documenting longer-term trends of changes and continuities from the baselines in 1995 and 2003, the effects of government policies and programmes and the effects of wider modernization processes in the different kinds of WIDE1/2 communities.

We drafted a research proposal for what would become WIDE3, also called ‘Long Term Perspectives on Development Impacts in Rural Ethiopia’. After unsuccessfully knocking on various doors we met the then Country Director of the World Bank, who had worked with anthropologists and drew on Alula’s Ethiopian expertise and who liked our proposal. With his support we obtained funding for a first stage of the WIDE3 research from a Joint Governance Assessment and Measurement (JGAM) trust fund financed by the British, Canadian and Dutch agencies/embassies in Ethiopia and managed by the World Bank. JGAM ended up funding all three stages of WIDE3.

We designed the research in successive stages: partly because it would have been very difficult to find a sufficient number of male and female Ethiopian social scientists understanding and interested by the approach and with the required language skills to be able to undertake research in all twenty communities at the same time; and partly because the complexity-informed methodology was quite experimental, and indeed evolved over the course of the three stages. As we explained to a senior government official:

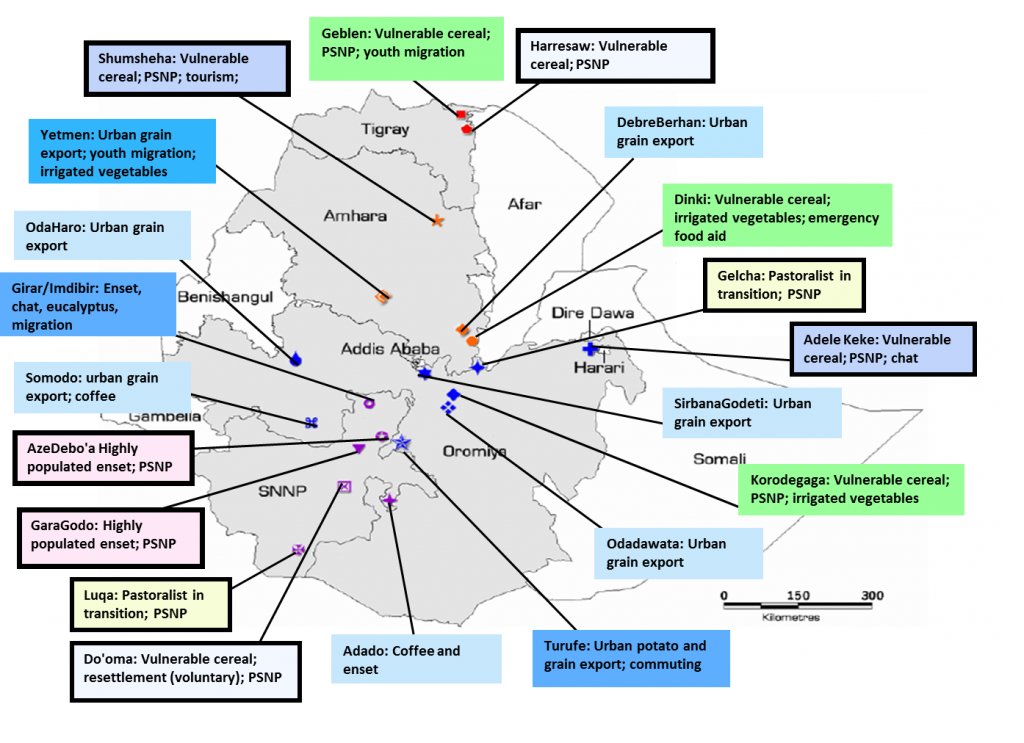

We are not economists or experts on any particular policy field; our approach draws on sociology and anthropology. We use theoretically-based and methodologically rigorous qualitative research to explore how communities with different types of key parameters (livelihood system, social mix, remoteness, Region etc.) have been functioning and changing since 1995 and especially since 2003 when Government interventions both expanded and deepened. Our research ‘tells the story behind the numbers’ and provides pointers to key issues for quantitative researchers and policymakers to pursue. The twenty communities are not ‘representative’ of all Ethiopia’s communities and the findings cannot be ‘generalised’ as economists would do. However, they are exemplars of many of the agricultural livelihood systems found in Ethiopia and of a wide range of other key parameters.

WIDE3 was organized in three stages, focusing respectively on: three drought-prone and three self-sufficient communities for which the baseline data was most extensive (Stage 1, 2010); eight food insecure communities (Stage 2, 2011/12); and six communities with different types of agricultural potential (Stage 3, 2013/14).

The WIDE3 research generated a wealth of raw data in the form of field reports, written by the Research Officers following research protocols designed under Pip’s lead. For each stage we analyzed this data in an intensive, iterative and cumulative process using multiple lenses. We drafted “community situation reports” for each community, followed by comparative analyses across the communities which culminated in three “short summary” reports highlighting the main findings of the successive WIDE3 stages. Limits in funding and time meant that by the end of Stage 3 we had not been able to do much cross-cutting analysis across all twenty communities. We surely will do this at some stage. In the meantime, here are selected highlights from among the main WIDE3 findings.

Selected findings from WIDE3 (2010–2013)

In all three stages we found that accelerating modernisation processes brought significant changes to the communities between 1995 and 2010/2013. Particularly since 2003 all communities, in different ways, had experienced economic improvements, lifestyle changes, improved service provision, increased access to justice, and declining gender inequalities. The pace of change continued to accelerate between 2010 and 2013.

Government interventions were key to progress in education and health service provision and women’s rights and opportunities. Infrastructure interventions (roads, phone network) contributed to lifestyle changes and improved access to services, and made a very significant contribution to local economic growth in all communities. Urbanisation and increased links with urban areas and in general with the outside world were generating big changes in lifestyles, especially for richer families, and in the local modern repertoire of ideas.

We also found that both drought-prone and ‘growth potential’ communities had seen economic growth, driven by improvements in agricultural productivity, increased demand for agricultural products, diversification outside of farming, better access to markets, inflation and new aspirations. Most notably in the Stage 3 communities with agricultural potential, farming was complemented by a wide range and increasing number of non-farm activities including increasing investment in land and businesses in local towns, small but sometime thriving private enterprise within and beyond the community (trade and services), community employment (local enterprises, government, daily agricultural and non-farm labour), commuting for rural/urban formal or informal work, and agricultural, urban and international migration for periods of varying length.

Farmers, traders and other business people were responding to market opportunities. However, the contribution of government-led direct economic interventions to local economic growth was uneven among the communities and on the whole not as high as it might have been. There was appreciation of some of the agricultural extension service focus. This varied across communities and included improved seeds and advice on agricultural diversification, advice on coffee growing and harvesting techniques and improved coffee varieties in coffee-growing communities, the introduction of hybrid breeds, better availability of veterinary services, etc.

As should be expected given the dimension of the challenge, there were also effectiveness issues. These included excessive focus on cereals and fertilisers compared to high-value crops; poor quality of improved seeds; inappropriate and costly fertiliser; high dependency on coffee in some communities; cash crop diseases not addressed; insufficient inputs of quality breeds, medicine, improved fodder and credit; and lack of government investment in irrigation. In several communities there were cases of pressure exerted on farmers to take modern inputs, which generated resentment. Livestock-rearing was profitable notably in communities close to towns with expanding demand for dairy products, but risky in the drought-prone communities, and these risks were not fully taken into account in government interventions.

Trade was largely left to private initiatives, with little support for investment by government apart from cooperatives – even, for instance, in the potentially profitable dairy sector. There was generally not much focus on non-farm enterprises apart from some credit, and, in Stage 3 communities especially, some land allocation, marketplace management and a growing interest in licensing and taxing. There seemed to be little budget to support micro and small enterprises. Lack of access to credit was regularly mentioned as an issue by poor people who could not meet the criteria for it and large businesspeople and farmers for whom the loans were too small and the processes too cumbersome.

It must be noted that these were not generalised issues and there also were signs of greater attention to a number of them in the Stage 3 communities.

We also found that while the range and reach of services available to the people in the communities had undoubtedly massively expanded, government services and policies were not reaching everybody, notably very poor and destitute people. There was increasing inequality within the communities: the rich were getting richer and the middle classes were better off and there were more of them, but there was still a substantial proportion of poor, very poor and destitute people. There were also signs of class formation due to the growing numbers of households with no or little land and the expansion of agricultural labour.

Moreover, the data suggested that for some of the poor the development intervention balance sheet was negative. Like other households they had to contribute time, labour and resources for the implementation of many interventions. Yet they faced barriers to access the benefits from these interventions, resulting from their lack of resources. While economic growth provided opportunities to some poorer members of the communities including through the provision of daily labour and commuting for employment, there remained a set of people who were unable to grab these opportunities in such a way as to reach a sustainable livelihood.

The youth also seemed to be missing out. With increasing pressure on land as a result of population growth generally and investment pressure in some communities, access to one’s own land was a distant or unlikely prospect for most of them. At the same time many young men with some education did not want to go into farming. Young women and men increasingly participated part-time in local independent agricultural and non-farm activities, but there were few full-time local opportunities for them. While youth might be particularly willing to engage in the growing non-farm sector, those who could not rely on their family for start-up capital and other forms of support had little chance of succeeding in the absence of government attention. There was patchy support for youth cooperatives with a mixed record of success. In 2013 a new initiative focusing on supporting investments in diverse activities by small groups of youth was unfolding but was at an early stage.

While commitment to education at all levels had increased, manifest unemployment and underemployment of young people with Grades 10 and 12 and even diplomas and degrees was generating some disillusionment with education, especially in Stage 2 and Stage 3 communities. Some young men endured periods of ‘lying idle’ while others migrated within and beyond Ethiopia. Young women unsuccessful in education had to choose between marriage and migration. Increasingly large numbers of them had opted for legal or illegal international migration, with significant economic and social consequences: remittances had changed lives in the community and in some cases raised the status of girls and young women.

Engaging with Ethiopian stakeholders – A future for WIDE?

Throughout the research we sought to engage with stakeholders – the Government of Ethiopia and also the community of donors, NGO people and academics with programmes or an interest in Ethiopia. However, we rapidly found that in some areas, donors and the government had quite different mental models of how development should be pursued, making dialogue between them complicated. It therefore seemed preferable to engage separately with each party. Our main vehicles for dialogue with non-government stakeholders were small workshops and meetings and presentations developed for these as well as research reports for each stage, and academic papers and presentations. We also seized opportunities to have dedicated meetings with government officials and sent shorter outputs to those who were interested.

Towards the end of Stage 3 in discussions with JGAM we considered how the WIDE3 evidence might be used to inform policy-making and implementation more directly. Five topic-focused discussion briefs drawing on the WIDE3 evidence were prepared by consultants (we provided inputs and guidance) and discussed at a High Level Discussion Forum with senior government officials in March 2014. It was gratifying to hear them expressing interest in the research findings and the reflections presented to them, after what had been a quite hesitant engagement process at times.

This, we believe, illustrated that one of the WIDE3 research’s major strengths as perceived by the Government of Ethiopia has been its independence from donors’ agendas and policy discourses, and the nuanced manner in which evidence-based suggestions were presented. Going forward, we believe that further thoughts should be given on how to strengthen independent, policy-relevant research in Ethiopia – including but not limited to WIDE.

Returning to WIDE, we all three are determined to take a break. However, we also very much hope that it will be possible to capitalize on the government’s interest and take the WIDE research forward in several ways. First, more could be done to draw on the existing data to make the research findings more easily accessible to policymakers and practitioners in Ethiopia. This holds both in terms of content, for example discussion briefs on other topics, and process, which might include joint government-donor discussion and involvement of regional governments. Second, we hope that it will be feasible to uphold the longitudinal character of this research. We have suggested that it would be interesting and useful to do a rapid round of going back to all twenty villages in 2015/16 which marks the end of the government’s current national development plan (the Growth and Transformation Plan/GTP) and the start of the GTP2.

Thinking further ahead, we hope that the WIDE research can find an Ethiopian home and, in its current or in a simplified form, become institutionalised as one of the ways in which the government and its development partners follow up on the long-term impacts of development interventions and broader modernisation processes in Ethiopia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.