Growing inequality as we grow economically?

Lilli Loveday

1 April 2014

/

- 0 Comments

‘Extreme disparities in income are slowing the pace of poverty reduction and hampering the development of broad-based economic growth.’

Kofi Annan, Africa Progress Panel, 2012

The issue of inequality is on the table – for all the wrong reasons. As the body of evidence pointing to the increasing gap between the world’s richest and the world’s poorest grows, along with evidence highlighting the negative ramifications, both socially and economically, of high levels of inequality, so too does the need to question the idea that economic growth will bring shared prosperity.

At Mokoro’s Quarterly Meeting (QM) in January, consultants and staff gathered to discuss the problems and drivers of inequality, as well as to add their perspective to the debate on possible solutions. This article brings an overview of the issue, prepared by Lilli Loveday, and a series of opinion pieces from Kit Nicholson, Bev Jones, Ray Purcell and Adam Leach.

The scale of inequality is shocking. Globally, we are experiencing the highest levels of relative and absolute inequality at any point in history. Figures indicate that the world’s 85 richest people own the same wealth as the 3.5 billion poorest people and that the top 1 per cent of the world’s population have 65 times the wealth of the bottom 50 per cent of the population. Economic growth has not been distributionally neutral, with the proportion of ‘additional’ global GDP going to the poorest 20 per cent of the population declining from 0.9 per cent to 0.7 per cent between 1999 and 2010 (UNCTAD, 2013). In other words, during that period for every $100 dollars of global income, only 70 cents went to the poorest quintile. Meanwhile, during a time of global financial crisis, the number of billionaires has increased by almost a third (from 8.5 million to 12 million). The problem does not only exist between developed and developing countries, it is also increasingly apparent within countries (and notably within developed countries). Between 2007 and 2010, OECD countries saw a greater rise in inequality than in the previous 12 years and it is estimated that almost one in ten working households across Europe are living in poverty. Inequality in Britain has recently come under scrutiny from Oxfam. At a time when over 500,000 people in Britain are believed to be reliant on food banks, it is entirely unsavoury and uncomfortable to learn that the single richest Brit is reported to own the same wealth as the bottom 10 per cent of the UK population (6.8 million people).

Despite growing consensus that inequality is an issue, it has taken time for the debate to catch up with the scale and urgency of the problem. At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, rising income inequality was tipped as being amongst the biggest risks for the coming decade. But this is in sharp contrast to statements made just over a decade ago. The 2000 World Development Report stated that rising inequality should ‘not be seen as negative’, so long as incomes at the bottom did not fall and the number of people in poverty did not rise. As such, halving the number of people living in extreme poverty (defined as anyone living below the conventional poverty line of $1.25/day) has been the focus of the development agenda for the past 14 years. But $1.25/day is a low and unambitious standard and with inequality soaring, many of the world’s poorest face more challenges than ever before.

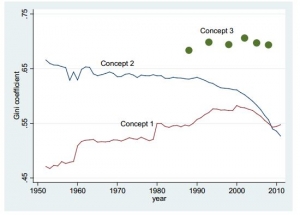

Note. The Gini coefficient measures deviation of income or consumption among individuals or households within an economy from a perfectly equal distribution (represented as 0). An index of 1 represents perfect inequality.

How inequality is measured is significant and the trend identified is dependent on various factors including the measure of inequality (e.g. Gini coefficient / Palma Index / Thiel Index); the unit of inequality (countries weighted equally or by population / individuals weighted equally); the income conversion rate used (purchasing power parity / market exchange rate); and the source of data (household income surveys / national income accounts). In a paper on the history of global income inequality, Branko Milanovic discusses three concepts of inequality:

Concept 1) un-weighted international inequality, measured by inequality in per capita incomes amongst countries in the world;

Concept 2) population-weighted international inequality (between-country inequality), measured by per capita income per person against their place of residence;

Concept 3) global interpersonal inequality, measured by calculating difference between actual individual incomes.

The distinctions are significant as the graph above highlights. Measured by concept 1, international inequality has increased between 1950 and 2010. However, measured by concept 2, the world appears to have become a more equal place. But concept 2 not only ignores within-country inequality, it is also skewed by the inclusion of China (and, more recently, India). China’s large population and rapid growth have offset slow growth elsewhere, thus distorting the figures. Measured by concept 3, where individual incomes are taken into account, there is a much higher overall level of inequality with a global Gini coefficient of around 0.70. However, lack of data from the poorest countries distorts the Gini coefficient down meaning that the true extent of global inequality may not be captured fully. This may explain the slight drop observed in the trend (which Milanovic describes as ‘a tiny drop, a kink’ (page 8)).

The associated issues of inequality are great, not least as a moral and ethical injustice. In an interconnected world, where we have greater dependence on nations, as well as greater awareness of ‘the other’ (including of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’), inequality impacts not only on financial and political stability but also on social stability. Furthermore, evidence indicates that no country has transited beyond middle-income status while maintaining high inequality, demonstrating how inequality inhibits development efforts. Recent reports by Oxfam highlight that economic inequality, if not addressed, could cost an additional $300bn in bringing an end to poverty. And, if inequality is accompanied by lack of publicly funded health and education services, there is an increased risk to people’s lives – especially the poorest – and exacerbation of social inequalities (such as gendered divisions in access to education) because these services becomes completely unaffordable. In a TED Talk, ‘How economic inequality harms societies’, Richard Wilkinson (author of The Spirit Level) draws attention to the ‘divisive and socially corrosive’ impacts of inequality. Focusing on the significance of within-country inequality, Wilkinson indicates that in countries where there is a greater level of inequality life expectancy rates are lower; there is worse social mobility and higher rates of homicide. Inequality brings higher rates of mental health problems and lower levels of trust, with Wilkinson referring to the psycho-social impacts of inequality – of feeling valued or de-valued, superior or inferior and secure or insecure. But as both Wilkinson and Oxfam point out, inequality isn’t just bad for the poorest in society (although arguably, its effects are felt most amongst this group), it affects everybody negatively – including the rich.

Addressing the issue is complex. Some argue that there should be a redistribution of wealth – with Oxfam claiming, for example, that if the income share of the richest quintile were to be reduced by just 1 per cent, an estimated 90,000 infants’ lives would be saved each year. The Brookings Institute further supports the potential of redistribution, indicating that it would only take a 0.25 per cent reduction of the top 10 per cent’s income to lift 154 million people from poverty over the next 10 years. Others promote economic growth and argue that if global inequality is primarily between populations in rich and poor countries, remedies should be focused on getting poor countries to grow faster. Milanovic makes a claim for increased migration and the need to ‘facilitate immigration in rich countries’. Other possible solutions include, improving taxation and the international tax system, ensuring delivery of free public services and devising progressive taxes for companies and individuals.

But for those who argue that inequality, instability and lack of cohesion are the mutually reinforcing by-products of finance-led globalisation, a far more drastic restructuring of the underlying economic system is called for.

You must be logged in to post a comment.