Catherine Dom reviews Land to the Tiller

Catherine Dom

11 September 2020

/

- 0 Comments

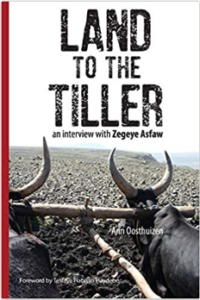

In this article Catherine Dom reviews Land to the Tiller: an interview with Zegeye Asfaw by Ann Oosthuizen. This is an interview with Zegeye Asfaw from 2012, telling the story of his life, of the struggle for land reform in Ethiopia, and of the personal cost of that struggle for himself and others.

Land to the Tiller is… a gem! It’s not just about land, it’s about history – which is all about land in Ethiopia as Zegeye reminds us; but it is also not just about history, it’s about the stories that make history happen. It’s also a personal life story, as a lens to think again about one of the – perhaps even the – most transformative moment of Ethiopia’s history of the last century, in a country that has seen quite a few ‘big moments’, and continues to try to find ‘a way’… And it is evidence that reforms can be tried ‘from within’, that this can be frustrating and defeated, but it can also succeed against the odds. Perhaps above all, for me, it is the story of a man who – with others – changed things in ways that mean ‘no going back’, because of his integrity, which nonetheless never prevented him from listening to people with whom he might not agree.

First and foremost, it’s the story of a man who has had an almost unimaginable life. Three times, under three regimes – the Emperor, the Derg who overthrew the Emperor, and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front who overthrew the Derg – he was a key actor in defining, or trying to define, how these regimes addressed the ‘land issue’ – one of two ‘most pressing’ and enduring issues in the history of Ethiopia. Twice, in these three times, he was a Minister, and twice, he went from that position to that of a prisoner, the first time, and of an exile, the second time. Add to that, in trying to protect his family from anything that could ‘backfire’ in the politically charged context of the Derg, he lost his wife’s trust and partnership whilst in jail. Many would have given up more than once. Not Zegeye, who may have kept his distance from Politics with a big P, but not everyday politics and the main thread of his life – how he could contribute to make things fairer, now working from the grassroots.

It is the stories that make history, for instance the story of the tenancy law. From history books we know what happened, how the Emperor told Zegeye and his colleagues working in the newly established Ministry of Land Reform to draft that law, for it to ultimately get blocked by the landlords who had the most to lose if it was passed, and the most influence on the Emperor. What is less well known, at least by me, is how the drafters, young idealists just out of their studies, thought that regulating tenancy was the most they could try to push for, but also that this could pave the way to organising and empowering tenants, which could in turn leverage bigger changes. That was not to be, at that time. But the idea of organising and empowering farmers, when Zegeye could go further and propose to abolish tenancy, as Minister of Land under the emerging Derg régime, was still there, and this time it was used.

This first attempt was also an example of trying reform ‘from within’ and failing. But years later, it worked, even though for that Zegeye had to take the risk of returning within from outside where he was exiled. As an OLF [1] Minister in the Transitional Government that followed the EPRDF [2] takeover of the Derg, he had to go away when the OLF felt they could not continue to be part of the transition. But when given a slim chance to work from within again and to join the Constitution drafting conference convened by the EPRDF under a moratorium of 40 days for exiles like him, he did just that, to defend the ‘land to the tiller’ reform he had driven under the Derg. And it worked. I am not a land expert, so I will not comment on whether private land ownership would have been better than the way land is still managed today in Ethiopia, as “a common property of the Nations, Nationalities and Peoples of Ethiopia”, with ownership rights vested in the State and the people, and usufruct rights for the farmers. What I can comment on, is how this work from within led to that outcome, and also how it was inspired by genuine conviction, but also a genuine willingness to engage with other opinions.

That is one of the most endearing aspects of the man, and a reason why this book has a lesson to tell… Zegeye listened and engaged with people, even when he disagreed with them or they were his jailors. He refused to see things and people in black and white, even characters like Mengistu. He wanted to understand all sides, and tried to convince others to do the same. The opposite of the ‘those who are not with me are against me’ position which too often has been how Politics have been defined in Ethiopia.

That is one of the most endearing aspects of the man, and a reason why this book has a lesson to tell… Zegeye listened and engaged with people, even when he disagreed with them or they were his jailors. He refused to see things and people in black and white, even characters like Mengistu. He wanted to understand all sides, and tried to convince others to do the same. The opposite of the ‘those who are not with me are against me’ position which too often has been how Politics have been defined in Ethiopia.

How did that come about? Maybe, this fact that in his childhood, when his family was discussing Oromo history which we are told all Oromo families do – for Zegeye is Oromo and Ethiopian – he was always told two sides of that history. The side of his father whose great grand-father helped Menelik conquer the Oromo land, and the side of his mother whose great grant-father was a key actor in the resistance against that conquest. Also, I believe, it was thanks to the power of education and what it does to someone and a whole generation to be exposed to ideas from outside, when this is combined with continued strong anchoring in one’s grassroots. Zegeye would not have been who he has been if his father had not at some point agreed for him to leave the family and go and study, OR, if he had let this cut him off from his roots – which he didn’t. Hundee, the grassroots NGO that Zegeye founded when he moved away from Politics – but not politics – means the roots of a tree.

Download the article here.

Robin Palmer has also reviewed ‘Land to the Tiller’ which can found on Mokoro’s website here.

[1] Oromo Liberation Front

[2] Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front