Reflections inspired by my advisory work for the Budget Strengthening Initiative programme

Catherine Dom

11 October 2012

/

- 0 Comments

The BSI model

It is for a little more than a year and a half that I have been working alongside a bunch of great colleagues for the Budget Strengthening Initiative programme (BSI), hosted by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). In this paper I share what are personal reflections arising from this work.

BSI is a ‘niche’ programme (as in ‘niche coffee’) in several ways. First, it specializes in supporting Public Financial Management (PFM) reforms – in fragile contexts exclusively. Second, it aims to do this ‘differently’, in providing advice to governments which is independent from donors’ agendas, requested by the governments, and kept confidential if they so wish; in drawing on a wide range of highly qualified expertise, top-notch research, and the energy and commitment of senior and junior BSI team members; in promoting peer learning across countries; and in linking up the PFM reform agenda with the broader agenda of transforming the way in which partners engage with fragile and conflict-affected states.

The ‘BSI model’ just outlined has arisen from the personal experience of the BSI director and from years of reflection by himself and others in research institutes, think-tanks and donor agencies about the particular challenge of building more effective, accountable and transparent budgets in countries in which the state is weak and governance is problematic.

BSI is currently active in three countries: South Sudan, Liberia and DR Congo. There is a crosscutting programme of research, including collaborative ventures with other parts of ODI and beyond, and a programme of policy and operational support to the g7+ group of fragile states.

BSI is funded by donor agencies, up to now mainly by DFID though this is due to change in the next few weeks. On the BSI Advisory Board sit other influential organisations including the IMF, the World Bank and the AfDB, all with big PFM agendas of their own. But, both funders and advisers on the Board have accepted to remain ‘at arms’ length’; the BSI teams are guaranteed to get the space needed to uphold the principles underpinning the BSI model. The principle of independent and confidential advice is particularly critical.

Should BSI be a mindset rather than a model?

In the past few months my mind has been exercised by the differences and similarities between the two BSI country programmes I happen to work for, in DR Congo and in South Sudan.

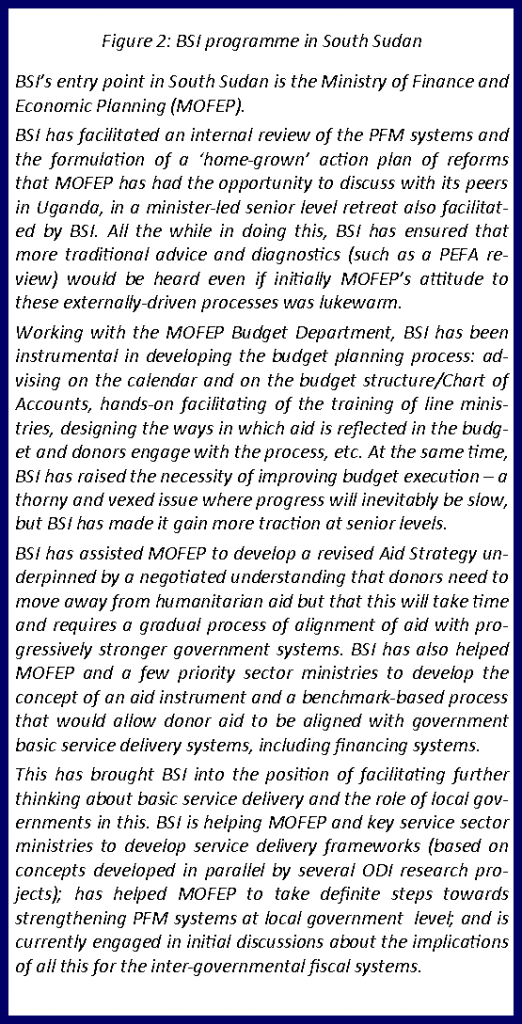

The BSI programme in South Sudan was the first (it started in 2010) and is the best-established (the country programme manager started working there on PFM and aid management related issues in 2007). South Sudan is a new country and even if it had some form of administration in the past, government systems are a new thing. Establishing sound budget systems and processes is all the more important to ensure best use of the country’s oil resources. With oil exploitation (interrupted for the last six months) hopefully resuming in the near future, South Sudan will have for the next few years a major and significant source of domestic resources compared to many developing countries, but with dismally low development indicators.

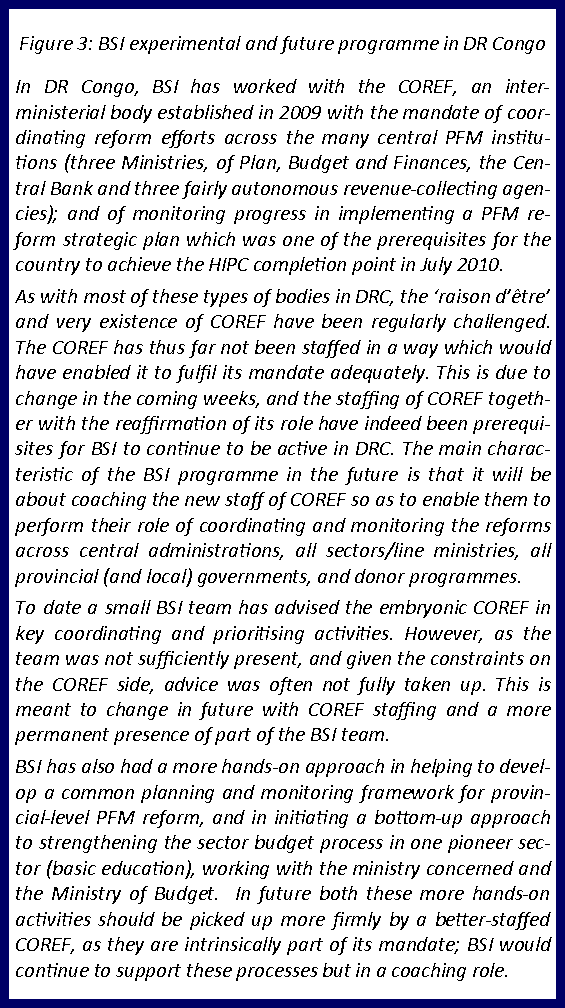

In DR Congo government systems have in the course of time since (and some would say from before) independence acquired a set of now deeply entrenched characteristics which make them feed off the citizens instead of serving them. For most people, their experience of the state does not match the concept usually associated with this word. There too, if governance in mining and natural resource management improved, the country would be vastly rich and the government budget much larger than today; in all likelihood this is a long-term prospect. The BSI programme in DR Congo has been called ‘experimental’ thus far. It is only now, after 18 months, that the BSI Advisory Board has given the thumbs-up for its expansion – on the basis that with the new technocratic government in place after the controversial 2011 elections there is a unique window of opportunity for much needed reforms, including of PFM systems.

Thinking about the shapes of the BSI programmes in these quite different country contexts I asked myself: Do we need or want one model, when we know that one-size-does-not-fit-all? Is it not more about a common mindset, but tailored models?

BSI roles in South Sudan and DR Congo

BSI roles in South Sudan and DR Congo

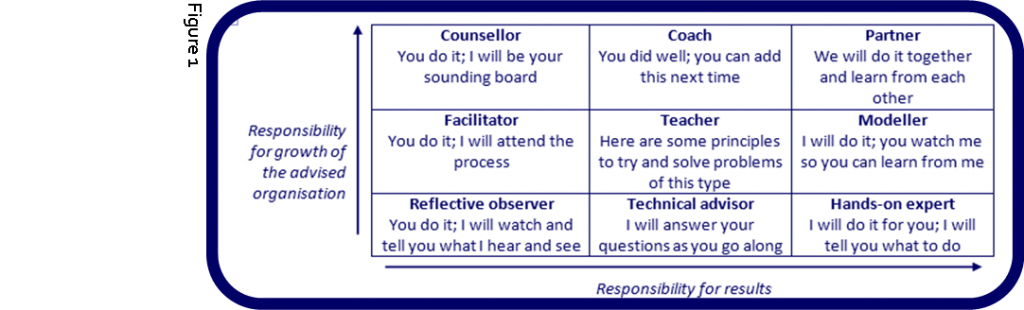

In the course of my reflections I was intrigued by the ‘consulting role grid’ of Champion, Kiel and McLendon (Figure 1). Nothing new, they proposed this grid in 1985! But to me, it is a powerful way of reflecting on advisers’ roles. It is noteworthy that already at that time the advice was to choose a consulting role through matching it to the situation.

The grid distinguishes nine possible advisers’ roles and matches them to nine ideal-type situations characterised by different sets of (hopefully agreed) expectations of what the organisation receiving advice might obtain from the adviser. These expectations are framed along two dimensions: (i) the extent to which it is expected that the adviser will be (co-)responsible for the results that the organisation has to produce (X-axis); and (ii) the extent to which it is expected that the adviser will be responsible for making the organisation grow in its capacity to produce the results without assistance (Y-axis).

A few thoughts came to my mind about where BSI programmes might fit in this. For instance, BSI activities would likely most often differ from reflective observation. Also, we would probably be wary of the ‘I will do it’ roles of the hands-on expert and modeller. Intuitively, most BSI advisory roles might belong in the middle column. I then looked at the two programmes that I know, the potted record of which is summarised in figures 2 and 3.

I would say that in South Sudan the BSI programme is more a combination of teacher and technical advisor roles, though with a bit of modelling and even hands-on expert roles – which has at times raised the question of the sustainability of the BSI-assisted activities. BSI is engaged directly with the government bodies (e.g. Department and Aid Coordination Directorates) in charge of both designing and implementing PFM reforms.

In DRC we may well have been in the same two main cells as in South Sudan (teacher and technical advisor). But this has been ‘messier’: among other things, we have had to spend time learning what the problems were and we started from a lower knowledge basis. Now the intention is to move towards a role of coaching the COREF. This means coaching not an implementing organisation but one which in turn will have to pick up the right mix of roles vis-à-vis the implementing actors. One question that the BSI team in DRC will have to address is what it takes to be a good coach for this particular type of organisation. One key element of response, in my mind at least, is that one cannot coach without oneself knowing the terrain quite well; and I would argue that it is impossible to maintain this knowledge without being at times fairly directly involved at the implementation level.

So, BSI as a model or as a mindset?

On the question of BSI as a model or a mindset, I came to a few tentative conclusions as follows. First, I would say that we have different BSI models in the two programmes that I know, in the sense of having different mixes of advisory roles; this is fine because the two models respond to different current country contexts, and different entry points, hence different natures of the organisations that are our main counterparts. But the programmes and models keep in line with the same mindset, in the sense of trying to make the mix match the situation. Second, I believe that the BSI model in a specific country will have to evolve over time – and that is probably something we will discover and should document. Importantly, these differences between programmes and their likely necessary evolution over time are not accidental but the result of efforts by the BSI team to acquire and maintain a distinctive ability to work in ways that are embedded and adaptive.

Bigger picture questions?

At the same time as the BSI teams were finding their way in the particular country contexts in which they work, the ODI-hosted Africa Power and Politics Programme (APPP) was making progress in “discovering institutions that work for poor people”. In their synthesis report (forthcoming) the APPP team makes a number of challenging propositions, including that

“More development support should be provided at arm’s length by organisations that may be aid-funded but do not disburse funds, solve problems as they find them on the ground rather than advancing a donor influencing agenda, have some freedom of action vis-à-vis their funders, use monitoring for learning and adaptation, have relevant technical skills but also local knowledge and long-term country commitments, and answer to local stakeholders (as a guarantee of the above, not for ‘country ownership’)”.

This, which chimes very strongly with the intended BSI mindset and ways of working, was arrived at through independent research focusing on both fragile and less or non-fragile contexts. I do believe that this rewarding endorsement of what we (the BSI teams) are trying to do (so far fairly experimentally) is more than a coincidental convergence. At the same time, I also believe that the APPP’s broader conclusions about ‘good governance’ should keep us (BSI) on our toes.

By now many of us recognise that “‘good governance’ as in Northern ‘best practice’ institutions doesn’t work, isn’t realistic, isn’t necessary and causes overload; case by case diagnostics are needed, to achieve ‘good fit’ with needs and possibilities”. But the APPP breaks new ground when it affirms that

“Governance challenges are not fundamentally about one set of people getting another set of people to behave better. They are about both sets of people finding ways of being able to act collectively in their own best interests”. If so, we should “understand governance limitations in terms of a web of collective action problems”.

Bringing this back to BSI… Let’s assume that we do not go to the point of questioning whether developing robust budget systems should be on the top list of ‘needs and possibilities’; the APPP proposition still begs fairly fundamental questions. For instance, what are the collective action problems that PFM reforms should aim to resolve, in country X at the time Y? And in this perspective, as inevitably BSI teams in-country become a part of the collective (and should do so if they are to be ‘embedded’), are some of the advisory roles more legitimate than others?

I will not try to respond to these questions here as I need a lot more time to reflect further…

You must be logged in to post a comment.