Are rubies undermining Maasai culture?

Jim Grabham

17 September 2019

/

- 0 Comments

Ruby mining is driving rapid expansion of the Tanzanian village of Mundarara. While earnings from mining are providing new opportunities for the majority Maasai population, two members of the community spoke to Jim Grabham about the socio-cultural impacts of the mining boom and the threats facing the pastoralist way of life.

Rosa Lopelel was returning from her daily journey to fetch water when we sat down to speak about life in a village that is now dominated by mining. Rosa was born in Mundarara in 1972 and lives with three generations of her family, rearing cattle, donkeys and chickens. With her grandson tugging on her robes she recalls what the village was like when she was his age: “When I was a child, there was not one single shop in Mundarara, we would have to walk a three-day round trip to Longido to buy anything. At the same time land was free, you could live anywhere, but not now.” Mundarara has changed considerably over the past four to five decades from being just a handful of pastoralist settlements to a vast village with a bustling centre focused around the market place, where brokers haggle over rubies while livestock roam between newly-built houses, shops and temporary settlements.

Rosa Lopelel returns home after collecting water

Rosa acknowledges that mining has contributed to the development of the village and gestures to the modern concrete building at the back of the family boma: “We built this with money earned from picking through the mining rubble and buying and selling minerals.” The family also owns a motorcycle and a building in the village centre, where Rosa lets out two rooms and uses the third as a shop, selling a range of goods to gemstone brokers and migrant mine workers.

Motorcycles are a common sight in the village as many families, including Rosa’s, invest mining profits in non-traditional technologies and livelihoods

Mundarara has experienced a proliferation of new permanent and temporary settlements in the last three years

The financial opportunities of mining are also recognised by Seembu Kipoyo, who lives an hour’s walk from the village centre in a traditional Maasai boma. Seembu has lived in Mundarara for more than 50 years but only got involved with mining in 2017 when he started brokering. For him, the chance to engage in the mining sector came along at just the right time. “The pastureland is not good anymore and it’s a struggle to keep livestock,” he told me. Seembu now walks to the village centre every day to spend time buying and selling rubies. He says his whole family now depends on him brokering the gems. While his income from mining is modest compared to others in Mundarara, he says it is enough to meet all his family’s financial needs. However, there are others in the village who have unearthed fortunes in the mines and gone on to construct large modern houses.

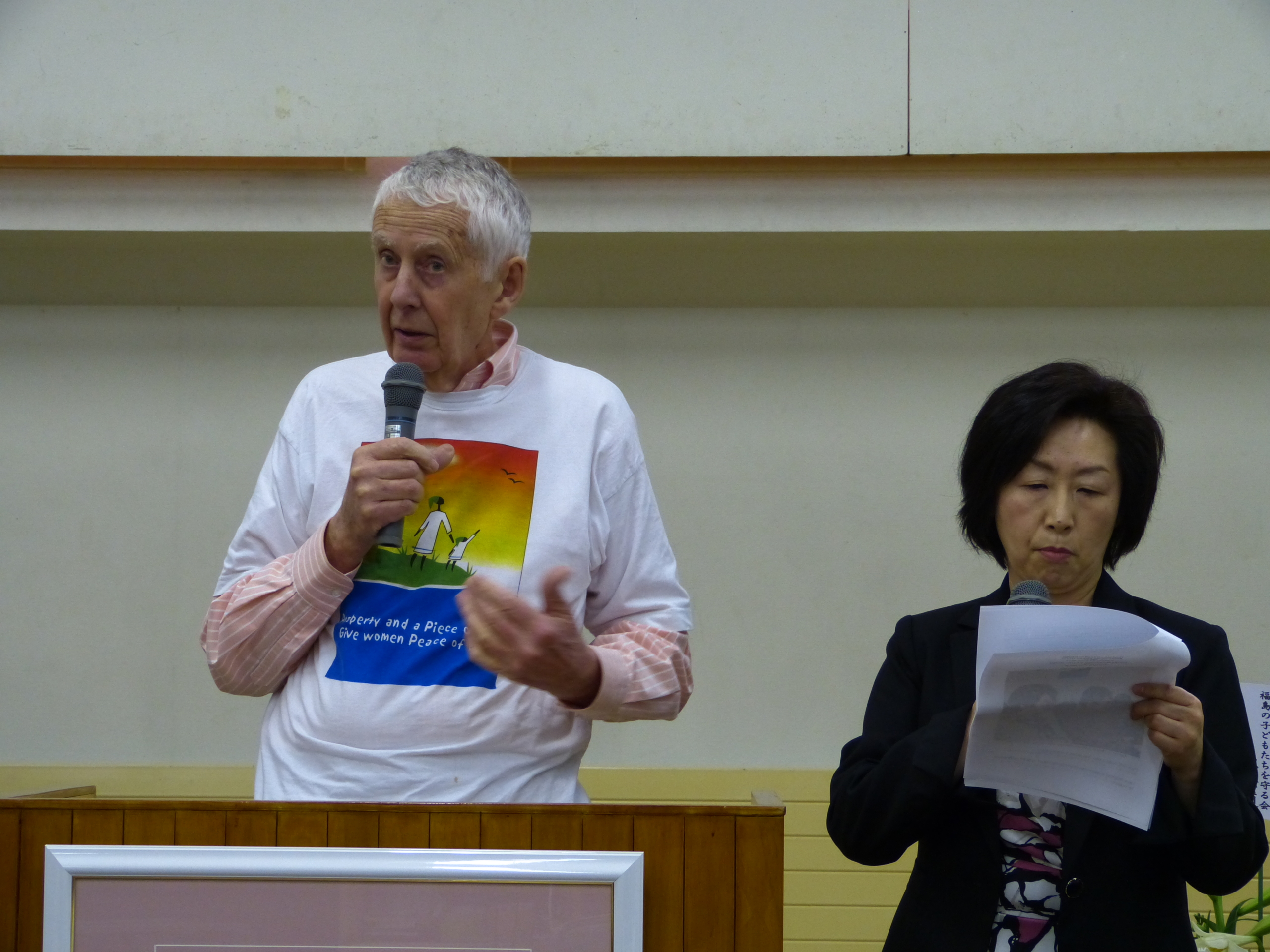

Seembu Kipoyo returns home

Rosa and Seembu are now both less reliant on livestock herding as a source of household income than in the past, and, as for many people in the village, their herd sizes have fallen. Yet any suggestion that herding is becoming less important for the Maasai is strongly refuted. According to both individuals, livestock husbandry is not simply a means to earn cash income, it constitutes a large part of their identity. Seembu put it simply: “Pastoralism is forever – you can’t milk minerals or eat them.” Rosa told me the Maasai will “always have animals – forever.”

Animal husbandry continues to have vital cultural and economic importance to the Maasai

For these two villagers mining is seen as a valuable short-term means to earn cash income, but there is a clear appreciation that the boom in the sector may not last for long. Pastoralism, on the other hand, is ingrained within the fabric of what it is to be Maasai. Seembu’s expectations of his family are clear: “Even if my children have PhDs and trillions of shillings in the bank, I expect them to come back to this village and care for their livestock.”

The changing socio-cultural practices are causing concern for Seembu, who claims that the money is becoming a problem and is changing people. The opportunities to engage in mining are particularly attractive for the younger Maasai who are exploring ways to spend their new-found wealth. Rosa shares this concern: “I want to see the Maasai wearing these traditional clothes, building the same bomas and tending to livestock, as these things give us our identity. I am proud to be Maasai but some girls now wear clothes showing off their skin and boys wear trousers low down, this is a great shame to the Maasai.” The influx of migrant workers from all over Tanzania is causing other social issues too, as Rosa explains: “They come to Mundarara and marry Maasai girls but they soon leave to go to other mining sites and forget about their wife.” Separations and divorce are far from common in Maasai culture and are seen to bring great shame to a woman and her family.

The largest mining site in Mundarara Village

These stories from the Maasai describe the complex relationship the village has with the mining sector. The growing wealth and access to new markets have undoubtedly contributed to economic growth and created opportunities for the local Maasai to pursue new income-generating activities. Furthermore, given the increase in desertification of grazing land and uncertain rainfall over the last decade, reported by many pastoralists during our WOLTS project research in Mundarara, mining offers them a critical safety net. Despite the opportunities brought by mining, the perception of many villagers I spoke with is that the mining sector is systemically unfair, with the majority of wealth finding its way to Arusha and Dar es Salaam, leaving limited lasting benefits for local people and eroding traditional livelihood practices.

Questions over both environmental and socio-cultural sustainability are a matter of urgency for future generations of Maasai if they are to continue living as pastoralists. My conversations with Rosa and Seembu show that real fear exists among the older generations that the Maasai identity is at risk if mining expansion continues on its current course.

Based on our fieldwork, one outcome of the WOLTS project has been the development of a programme to support people like Rosa and Seembu to become champions within their villages, able to help their communities to strengthen the inclusion and participation of all community members in protecting their pastoralist way of life.

Rosa Lopelel has been involved with the WOLTS project since early 2018, championing women’s rights and spreading awareness within Mundarara about mining and land laws

Rosa Lopelel and Seembu Kipoyo have taken part in a one-year training programme on gender, land and mining carried out by HakiMadini and Mokoro under the WOLTS project. Twenty-six community members have been trained in Mundarara to be champions of positive change, able and ready to support their neighbours and village leaders in protecting village land and natural resources in a gender-equitable, participatory and culturally sensitive way. Read more about the WOLTS project here.