Land advocacy in Africa, past present and future

A Mokoro Seminar

Rebecca Aikman

13 April 2017

/

- 0 Comments

Livelihoods, food, shelter , identity: for millions of women and men around the world, land and its related resources are central to survival. Three out of four people currently living in poverty survive on farming[1] as a means of supporting themselves, their families and communities, which places the role of equitable access to land very high in the order of global development priorities. Land reform, which relates to the remodelling of tenure rights and the redistribution of land in a way which is consistent with the political directions of reform,[2] promises to make significant advances in promoting equal land rights and reducing rural poverty. There are numerous approaches to land reform, including state-led and market-based interventions. Redistributive land reform, which has been delivered in a variety of different forms, has achieved success in some areas and we now have many interesting cases studies to review to generate lessons for future land reform.

, identity: for millions of women and men around the world, land and its related resources are central to survival. Three out of four people currently living in poverty survive on farming[1] as a means of supporting themselves, their families and communities, which places the role of equitable access to land very high in the order of global development priorities. Land reform, which relates to the remodelling of tenure rights and the redistribution of land in a way which is consistent with the political directions of reform,[2] promises to make significant advances in promoting equal land rights and reducing rural poverty. There are numerous approaches to land reform, including state-led and market-based interventions. Redistributive land reform, which has been delivered in a variety of different forms, has achieved success in some areas and we now have many interesting cases studies to review to generate lessons for future land reform.

Looking ahead, however, there is increasing pressure on land. The past decade has seen soaring world food and commodity prices, increasing the political and commercial value of both fertile land and water to new heights. Extractive industries have further fuelled rising prices, as the rush to exploit oil, gas, metals and mineral resources intensifies. Land inequality continues to disproportionately disadvantage those most impacted by rural poverty. Women continue to be denied the right to own, manage or inherit land in more than 50 per cent of countries worldwide.[3] Meanwhile the relationship between access to land and conflict is well documented, with unequal land rights both the cause and the result of conflict across the globe.[4] The need for progressive land reforms, to be underpinned by strong land advocacy, is therefore imperative.

On 10 March 2017 Mokoro held a well-attended seminar on issues relating to land advocacy in Africa which provided space for members of Mokoro’s land, livelihoods and natural resources team to share a platform with speakers from academic institutions. The seminar was chaired by Robin Palmer, who spoke of his initial engagement in land advocacy in Rhodesia back in the 1960s, and then mentioned the Land Rights in Africa website, now based at Mokoro, which he has managed since 2000, and which currently contains 983 entries. The seminar comprised a panel of four land experts – Martin Adams, Chris Tanner, William Beinart and Rachel Ibreck – who presented perspectives on land advocacy from Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and South Sudan.

Land Reform: Southern Africa 1990-2010

Martin Adams is a land policy and land administration specialist with diverse experience in Africa, South-East Asia, the Middle East, the Pacific and the Caribbean. His presentation compared his experiences from Namibia with those from South Africa, both at crucial moments in the history of land reform in the region.

In 1990, having gained its independence, Namibia took time to think seriously about land reform. The Namibian experience provided an example which others have appeared to follow, most notably South Africa.

At the time, land reform was synonymous with the repossession of land that had been taken by white farmers, amounting to 50 per cent of the land available. Martin reminded us that land is a justice issue; in Namibia land was used as a tool for the suppression of the people, who were expected to work for their oppressors on lands which they were denied the right to own, manage or transfer.

Martin spent the first six months of 1991 assigned to the Namibian Economic Policy Unit (NEPRU) to help prepare for a national conference on the land question. There were over 500 participants, brought from all parts of the country. The injustice felt by the dispossessed was strongly expressed at this meeting – land users who had been stripped of their rights sought the return of their access to land. However, eventually it was agreed that formal land restitution would not be possible owing to the impossibility of identifying ‘who occupied what and for how long’.

The conference recommendations included that foreigners should not be allowed to own land, absentee landlords should be expropriated, very large farms and ownership of several farms should not be allowed, and the conditions for farm workers should be improved. It was also suggested that “communal areas should be extended where necessary”. There was also a prominent view that freehold farms should be available to black farmers, supported by white farmers keen to recruit politically influential black farmers to their ranks, black businessmen and government officials keen to own farms, and small farmers in communal areas.

The first measure following the conference was the establishment of the Affirmative Action Loan Scheme introduced under the Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Action 1995, with the purchase of commercial livestock farms at market prices for redistribution to the poor. However, such schemes had not been viable elsewhere, and subsequent evaluations showed that AALS enterprises were only economically and financially viable where livestock farms had sufficient access to finance to service loans and to enable them to survive drought, predations and diseases.

In 2002, after the fencing of communal land had been proceeding apace, Namibia followed the Botswana example and established statutory land boards under the Communal Land Reform Act, which retained local chiefs as advisers, giving them the authority to approve or revoke land rights. The issue of dual grazing rights, whereby large commercial farms would graze their animals in communal areas during the dry season and return them to their own land during the rains, continued and many communal lands were illegally fenced off by more affluent farmers. Requests for extending communal land were ignored as this was at odds with the requests of the more prosperous farmers who were engaged in ranch farming only. Problems related to the powers and accountability of traditional leaders for their decisions relating to land allocation and limited regulation of the allocation of large tracts to foreign companies. Without protection of ordinary rights holders to commonages and accountability of traditional authorities, land grabbing of various forms is likely to continue.

Martin noted that many of the proposals raised at this time were not listened to, a parallel with his experiences in South Africa where he worked initially in 1993 for the Land and Agricultural Policy Centre (LAPC), an ANC think tank, and then from early 1995 for the Land Policy Division of the new national Department of Land Affairs (DLA).

South Africa was also undergoing a period of reflection regarding land ownership and repossession. By 1957, 89 per cent of available farm land had been taken by white farmers, and by 1990 calls for justice in land reform were heard loudly across the country. Martin spoke with further ‘justifiable pessimism’ (as he put it) regarding the achievements made during his time in South Africa. Although he was formally at the centre of the land reform movement during his time at DLA, he noted that in reality many hands were stirring the pot: national government, the ANC, commercial farmers and civil society organisations all had significant influence on the policy. Though there were demands for justice through land reform, these demands were constrained by the World Bank and other donors, whose focus was on making land more productive. As Martin noted, the struggle between justice and the interests of agricultural production is really at the heart of the land reform question.

A two-year pilot programme was got under way whereby grants would be given to households to purchase farms. Problems included that because land was costly and unavailable in small grant-size parcels, poor people had to form possibly dysfunctional groups to obtain grants, resulting in scattered projects often without necessary physical and social infrastructure, and there was inadequate capacity to implement the programme and provide legal advice and other support. Between 1994 and 2000 only about 0.8 per cent of the country’s agricultural land was transferred to 56,000 black households. Following the general election in 1999, grants of up to 80 per cent were provided to prospective farmers to purchase small and medium-sized farms. By the end of 2005 land redistribution had increased to 3 per cent of the total area of agricultural land.

The Bantustans – the former ‘homelands’ – were passed back to central government control in 1994, and Martin worked on the Communal Land Bill, which was to come before Parliament in 1999 for approval. ‘Permits to occupy land’ were to be replaced with enforceable rights within a unitary non-racial system of land tenure. However, it was not to be – the bill was unpopular with the traditional leaders who argued that under customary law they were the custodians of land rights and must now be legally recognised as such, and it was sacrificed in exchange for their support in mobilising the rural vote for the ANC.

Martin remains positive despite the setbacks during his time in South Africa and Namibia. He warmly remembers his time in South Africa as being especially stimulating, despite his concerns that what they set out to achieve was beyond reach. He is encouraged by his ongoing work with civil society organisations across Africa, who reassure him that the struggle continues and provide him with optimism for what is yet to be achieved.

Martin’s presentation is available to read in full on the Mokoro website.

Struggling to implement a progressive land law in Mozambique

Chris Tanner has over 30 years of experience in rural development, land policy and legislation, sustainable and equitable rural development, and community-investor land partnerships. He was a Senior FAO Advisor on Land and Natural Resources in Mozambique, where he was involved in the development and roll-out of the Mozambican Land Law, for 11 years, and since joining Mokoro in 2012 he has focussed on inclusive business models and local land rights, community and women’s legal empowerment, and land governance.

In Mozambique, as elsewhere, the challenge was in securing local land rights whilst simultaneously generating investment. An approach which acknowledged customary rights, reflecting how land is used using a productive system analysis, was perceived to work best. The Mozambican Land Law was approved in 1997 after the framework was accepted by the government and a methodology for delineating customary land use was subsequently established using analysis of production systems in each area, giving a broader sense of the use and historical occupation of the land. A specific local community was then delineated with legal access to the land for its use and benefit.

A system of mandatory community consultation was established, in which investors would be welcomed to bring investment, employment, capital, community projects and infrastructure to a community and the community would be encouraged to negotiate the terms for access to the land, using any income generated to upgrade their agricultural systems.

Chris noted that 20 years on the programme has been operating as expected or in part in some areas of the country and it is thought that 25 per cent of Mozambique is now delineated. The law enjoys strong donor and civil society support. However, reform efforts have been hampered. Chris saw the core constraints as being weak land management (which has not been addressed given that it benefits the elite), a failure of institutional reform, and elite and political resistance to the model. The state has also sought to reinforce its power through land and several state-aided ‘land grabs’ are thought to have taken place under the guise of the Land Law. The situation is increasingly characterised as a class struggle whereby ordinary citizens are pitted against elite groups and big capital in trying to achieve and protect land rights.

Alongside the implementation of the Land Law, the FAO has established a paralegal programme to support the empowerment of local communities and district level local government in understanding the law and its uses in order to achieve change. Chris saw this approach as fundamental to tackling the need for civic education and ‘democratic skills’ if the potential of the Land Law is ever to be realised.

Looking ahead, Chris saw the solution to this inherently political problem to be political and he reminded us of the potential impact of political activism in the continuing struggle for land rights.

Restitution, mining and land rights in the former Transkei, South Africa

William Beinart is an historian who is now an Associate of the African Studies Centre, University of Oxford. He was Rhodes Professor of Race Relations in Oxford from 1997 to 2015. His current area of research includes agrarian history, rural governance and land reform in South Africa.

Between 2007 and the present day, William has been acting as a researcher and expert witness for the Legal Resources Centre, Johannesburg. This has included working to achieve resolutions to three land restitution cases which he discussed in his presentation. Restitution has been a central pillar of the land reform programme in South Africa. These cases involving restitution focus on lands in the former homeland of Transkei which were seized from communities by the government for commercial purposes. The first was a case in which 1,200 hectares of land were taken from 900 families for a sugar scheme. The case was initially lodged in 1995 and faced resistance from both the government and local chiefs. It was finally heard in court in 2009 and the court decided that the land should be returned to the community. Disappointingly, since this outcome no changes have been reported. The second case was that of the ‘Wild Coast Sun’ casino built by a large international corporation which seized 750 hectares of land from the local community for the development. Restitution was opposed by both the corporation and the government. This case was eventually settled out of court in 2014 and a settlement favourable to the local community was reached. Again, disappointingly no movement on the process of restitution has as yet been reported. The third case centred on an area which had quartzite soil containing rare minerals of interest to mining companies. Local communities were removed from the area and a mining licence was issued. Following the legal challenge, the Minister of Mines has suspended all possible mining until the case is resolved.

After more than 20 years and despite multiple efforts it has still not been possible to establish ownership of lands in the former homeland areas. The rights to many areas of land there have been transferred. As in Mozambique, external agencies are increasingly a threat to local peoples’ rights. The enormous expansion of mining has had a significant impact, with mining activities often taking place in dispersed geographical locations owing to the kind of minerals exploited.

William raised the issue of ownership as a notion in promoting communal land rights. Whilst the issue has long been a contentious one, in a seminal legal case it was decided to award restitution of land along the west coast of South Africa, where the land appeared to have been bestowed upon the community in a system of customary/indigenous ownership. In this case, the notion of ownership was used to show the strength of connection with the land. It was highly significant that the Constitutional Court was willing to accept this notion of ownership as it conceived of ownership as a communal right.

Also of significance, the court in the first case recognised the notion that it was not the whole community that owned the land, but only a specific group of claimants which had a claim to indigenous/customary ownership.

William also spoke of the potentially harmful influence of the traditional authorities, who may be drawn in by promises of political or economic gain to assist in the forceful removal of people from their land.

Looking ahead, William supported the movement to redefine community below the level of chieftaincy and also to push for land reforms which seek to acknowledge community along the lines of a common sense of purpose rather than as a geographical area. He also sought to establish recognition that customary systems don’t require common usage, at least in residential and arable areas, but are rather inherited – not by individuals but through families and generations. He perceived this notion to be essential for winning cases and also for establishing a protocol for families to be consulted on land access in future. He was critical of the impact of legislation, which in his view has allowed land to be appropriated. New legislation from government authorities was currently pending. William suspected that it would unfortunately be weighted in favour of traditional councils.

William was still interested in the old idea of a land register, which could act as a system of protection and allow registration at the level of the family to take place. A contentious point, but William could almost conceive of advocating for titling as there is a concern that the South African Government is unlikely to oppose the chiefs who are likely to reject any system of land registration. Whether titling or implementing a system of registration, William advocated a system which would provide ownership at the family level and the strongest possible rights under the law.

Customary authority, local patronage politics and land grab advocacy in Africa

Rachel Ibreck is a Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research includes a focus on land conflict, including transnational and local resistance to ‘land grabbing’ in Africa. Her expertise in this area is based on interdisciplinary academic research and activist engagement.

Rachel presented two contrasting cases, viewed in the context of the post-2007 ‘great African land grab’. Both struggles were concerned with governance and political authority: the question of who has the power to decide on land reforms and land deals. As with the other speakers, she was keen to examine the ways in which customary authorities can be allies in opposing land grabs or can be associated with the process of elite capture.

The first case study was from Sierra Leone, where land is treated as a social good and in the majority of the country is held under customary tenure. Corporations are expected to negotiate land access with the relevant communities. Local chiefs, acting as intermediaries between the state and the rural people, also act as custodians of the land in supporting decision-making processes around land use. The site in question experienced a sudden influx of investors during the post-2007 food crisis, and a deal for a multinational to establish a palm oil and rubber plantation was reached. Unfortunately this deal had a significant negative impact on the community, including damaged nutrition and livelihoods for local people even though a consultation process had taken place and the community was engaged in the decision-making. The community had effectively been steered towards supporting the development by the paramount chief who warmly endorsed it. On recognising the issues relating to the development, the community then sought to end the project, initially mounting a peaceful protest. However, as tensions rose, some community members were arrested for damaging oil palms in an act of defiance. This example demonstrated how tensions around land use can lead to conflict.

In South Sudan, Rachel conducted research on an area in which conflict was both fuelling and exacerbating tensions around land rights. In the midst of civil war, with mass atrocities and mass displacement, an area just across the border from Uganda became the centre of a struggle for land between a local community, businessmen and the traditional authority. With the outbreak of war, the formerly rural area became highly valuable owing to its road access, proximity to the Ugandan border and access to food supplies. Customary land tenure was in place, and the South Sudanese constitution upheld the principle that ‘the land belongs to the people’. There was an attempt by some local businessmen to acquire and commodify the land for their personal gain, against a backdrop of rising land prices and considerable commercial interest. Their efforts were initially bolstered by the support of the paramount chief. However, he soon withdrew his support under pressure from the local community. He was killed following his change of mind, and several community members were accused of causing his death, leading to an increase in community tensions and the emergence of a violent resistance which became part of the broader context of violence in the wider situation. Recognition of the relationship between peace and land reform was observed in the inclusion of land reform in the failed peace deal.

Rachel reflected on these case studies and their significance on the issues of land, the local authorities and the crisis of governance. Looking ahead, she encouraged us to consider the restructuring of relations between the citizen and the state as a means of addressing the land question.

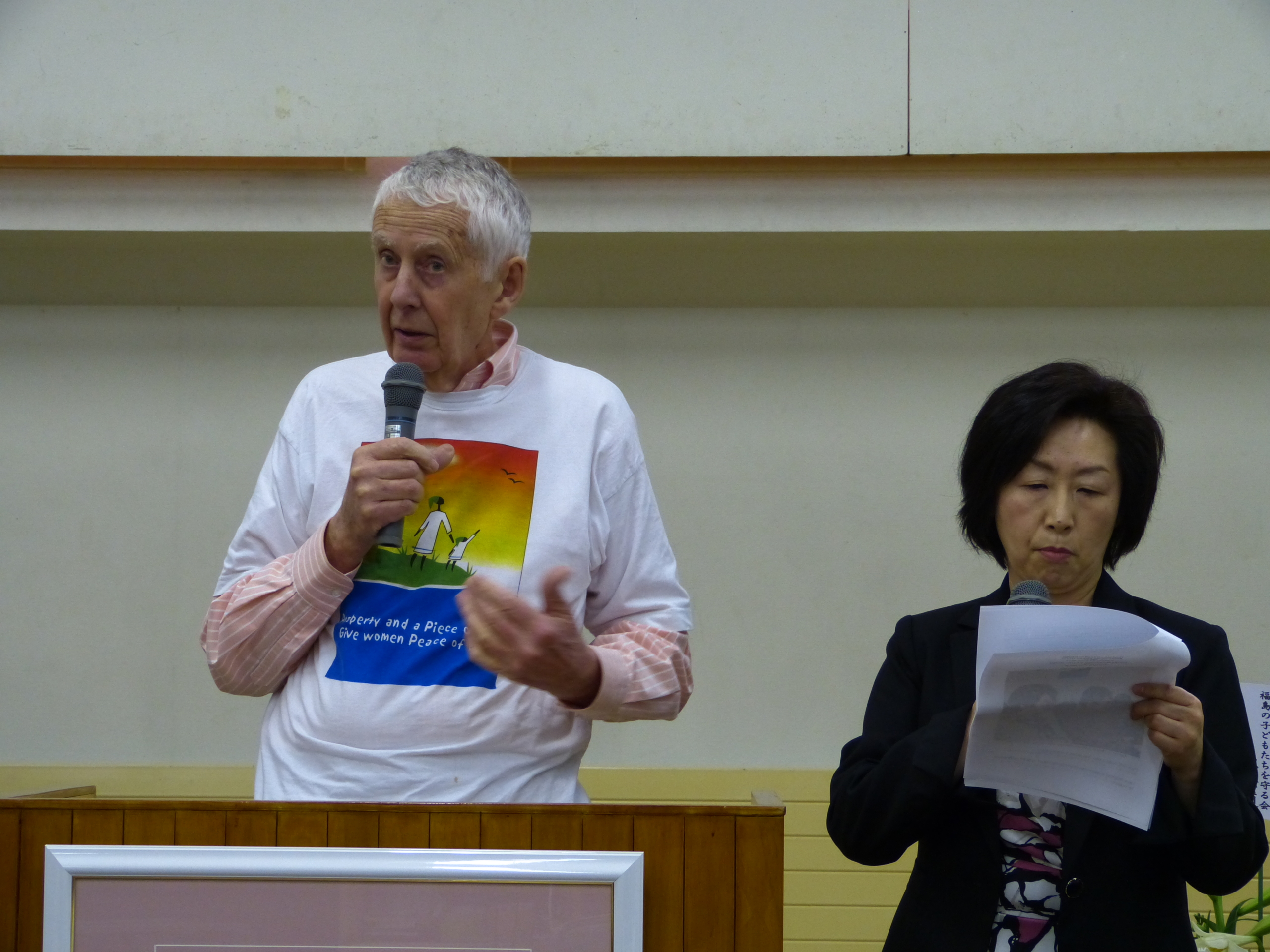

Interesting questions and discussions took place after each of the presentations in the seminar. There then followed a separate, but linked event – a showing of the truly remarkable film Land Grabbing. Mokoro was honoured by the presence of the film’s Austrian Director, Kurt Langbein, who had flown from Vienna in order to answer questions about his film, which contained examples of land grabs from Cambodia, Romania, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Sierra Leone. The questions clearly reflected the strong impression the film had made on the audience. The film is the subject of a separate article which can be read here.

[1] http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/our-work/land-rights

[2] https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/2979.pdf

[3] http://www.landesa.org/resources/property-not-poverty/

[4] http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01066/WEB/IMAGES/109509-2.PDF

You must be logged in to post a comment.